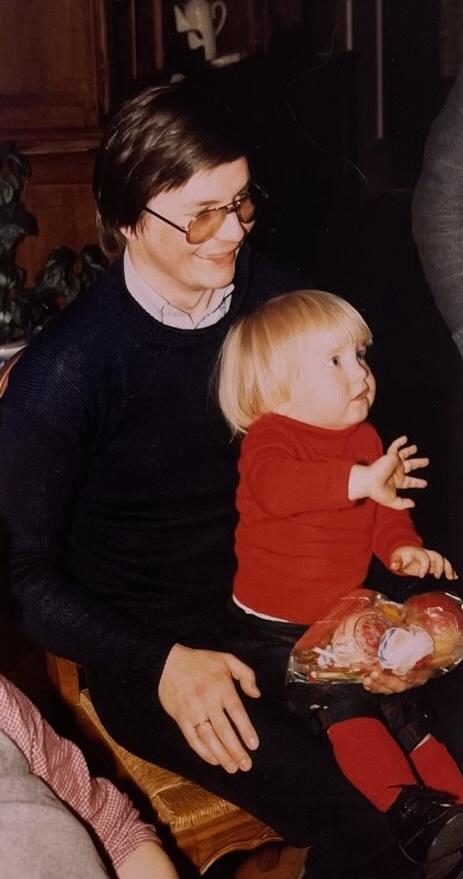

The first thing I notice is the young boy's frightened gaze. His eyes are widening, his gaze is fixed on something specific, something beyond the frame of the photograph. The impact of it, though, can be traced in the boy’s body and posture. He looks upwards, tilts back his head and tucks in his shoulders, recoiling from whatever is approaching him, bracing for impact. With his right hand he makes a helpless gesture, a futile attempt to maintain some distance between him and the source of his fear. What is he frightened of?

I am intrigued by the boy's expression because of how it contrasts with the expression of the man. The boy must be about two years old; and the man, I surmise, is his father. Initially I am captivated by the boy. I start tracing the trajectory of fear as it rapidly traverses his body. Like a lightning bold it branches off instantaneously, electrifying the boy’s entire being. But halfway through I startle. I now notice the man’s relaxed demeanor. Interrupting my labyrinthic exploration of childhood anxiety, I examine the father. His right hand is resting on his thigh, making no effort to protect the child. Looking at his face, I am surprised. The father appears to derive a certain pleasure from the boy’s anxiety. How can that be?

The contrast between father and son intrigues me. Not only because their emotional states stand in almost perfect opposition to one another. Sadly, the joy derived from other peoples misfortune, also known as schadenfreude, is part and parcel of the world we live in. This I know. But I also know the man in the photograph. I know him well, almost like I know myself. And in all the years I have known him I have never once witnessed him deriving pleasure from someone else’s distress. Rather, I know the opposite to be the case. I know this because I am the father’s son. I am the young boy sitting in this man’s lap. And while I have no recollection of the moment that this photo was taken, I vividly remember the countless conversations we have had on the subject of empathy during my childhood; one conversation for each time I had rejoiced in the pain of other beings. Inexhaustibly and patiently my father would guide me back toward the path of empathy.

This is why the tableau of oppositional emotions puzzles me. Inadvertently the photograph has captured a moment in our shared lives that stands in direct contradiction with what I hold to be true about my own upbringing. How can this be? What is happening here?

The second photo brings some clarity. It was taken just moments after the first one, on the morning of December 6 1981. My father and I are in the house of my maternal grandparents, situated in the rural outskirt of Belgium just a few kilometers from the Dutch border. The entire family has come to the house to celebrate a folkloric festival known as Sinterklaas. Until recently the saintly figure of Sinterklaas was flanked by a racist stereotype known as Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). In the photo, the figure leans over the boy and takes his hand. Antiracist activists have poignantly and consistently pointed out the deep racist nature underlying this folkloric tradition as early as the 1980s, when this photo was taken, and long before that. But that message had not reached the rural region in which I grew up; or if it had, it was stubbornly ignored. Coming across these photos after so many years, I find myself witnessing a painful scene. This is embarrassing and I am tempted to look away, discarding what I see. But after a short hesitation, I keep my eyes on the photos and study them more closely.

The interaction between the father’s pleasure and the boy’s fear is an intimate family affair. But it is not, I believe, a simple display of personal feelings. I find myself looking at a moment at which a societal sentiment is inscribed onto the body and mind of a two year old boy. I know that the joy of the father is not evidence of his personal inclination toward schadenfreude. The space in which this pleasure can emerge is opened up by the father’s assessment that the figure standing in front of the boy is harmless. He feels no need to reassure the boy, as he would normally do, because he knows how the scene will unfold. Soon enough the boy will realize that the intimidating figure of Black Pete is harmless. His anxiety will make way for joy; his feelings will realign with those of his father, creating an intimate bond between the two of them. I suspect that the anticipation of that moment is the real source of the father’s joy. In the second photo, I notice the father looking at the boy, eagerly anticipating for the boy’s expression to change from fear to joy.

The absence of immediate harm is what allows this scene to unfold, but it also enables the inscription of a deeper harm. Neither the boy nor the father recognizes the racist stereotype of Black Pete for what it is. The father, familiar with the Sinterklaas tradition, finds joy in a ritual carried over from one generation to the next; the boy, faced with a grotesque caricature and fearing harm, is inadvertently instructed to read the Black body as dangerous. Both emotions are obtained through the same racist caricature. The coincidence of these feelings is not accidental, and neither are they purely personal. They structure the culture and society in which the father and the boy live.

The father is not wrong. Soon enough the boy’s anxiety abates, though not entirely. It cannot. The singular thrill that gives the Sinterklaas festival its unique cultural flavour, the anxious excitement and hopeful anticipation it elicits in many children raised in the Low Countries, can only be achieved by a mixture of joy and a residue of fear. As the years go by the boy becomes oblivious to the source of that fear. He is only vaguely aware of the cloud that eclipses his feelings about the festivities, and he remains blind for the grotesque and hurtful caricature at the centre of it all. Unbeknownst to himself, the shadow of racism shades his understanding of the world.

In the decades that follow, the boy slowly begins to recognize the patterns this shadow throws and the path it has carved out for him. Now the real work begins. Tracing back his steps, examining the social structures shaping his feelings, the protracted journey of unlearning commences. In all likelihood, the shadow will never quit disappear. No soul is spotless, some stains will remain.

I remember the moment when I first became conscious of these photos. I had seen them before of course. Along with many other snapshots from my childhood they lay dormant for decades in an old family album, which was stored in an old shoe box, which was kept in an old cupboard in the storage room of my house. But I had not really taken them in. Until one Saturday morning a few years back. It is early spring and I am cleaning the storage room, eager to be distracted from my chore. Halfway through my work I encounter the box. I open it and start peruse through the album. Then I see these photos. For the first time perhaps, I really see them.

I discarded several items stored in the cupboard that day. The photos I kept. From time to time I take them out and study them. No matter how long I look, a shadow of doubt remains. How much has this impacted me? How do I unlearn this?

Story by bram ieven.

bram is a researcher, writer, and musician who works on play, new media, art and popular culture. This serves as a basis for narrative essays and audio stories that intertwine personal experiences with a reconstruction of seemingly insignificant historical moments or cultural events.