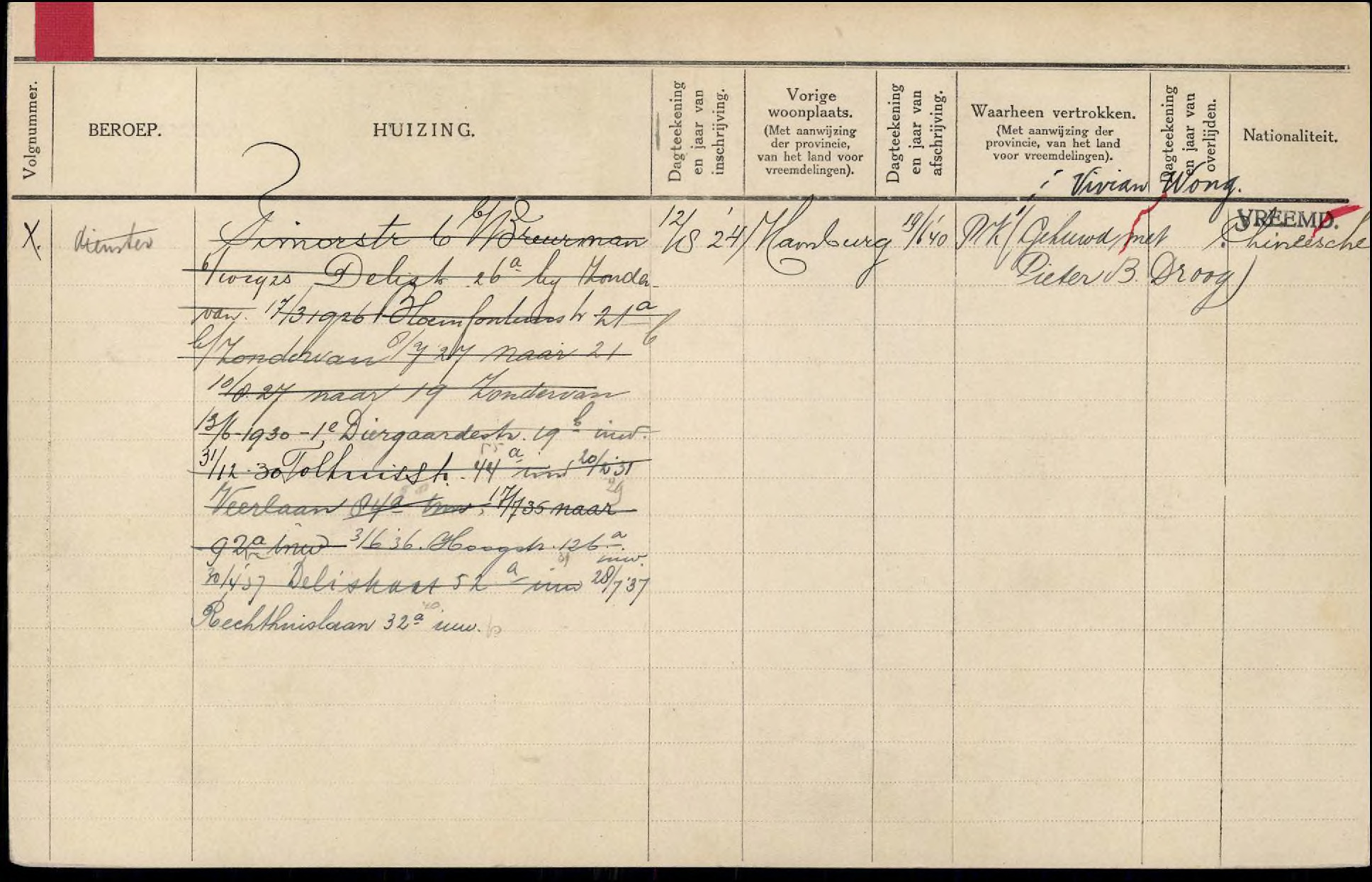

This document from Rotterdam’s population register captures the existence of Vivian Wong, a woman born in 1916 in Hoboken, New Jersey. Before arriving in Rotterdam, she travelled through Hamburg, possibly through the Hamburg America Line. She registered her first address in Rotterdam, in 1924. On 19th June 1940, more than a month after the Dutch forces surrendered to Nazi Germany, she married Pieter B. Droog. Under the occupation column, an administrator scribbled dienster in pencil and then crossed it off with pen. The term can refer to “maidservant” or “waitress.”

Family Cards, or Gezinskaarten, were used to record municipal population in the Netherlands. It captured details such as address changes, nationality, and marital status. Vivian Wong’s card stood out to me because most Chinese living in Rotterdam in the early 20th century were sailors and dockworkers – jobs dominated by men.

Vivian Wong was Chinese. She lived in Katendrecht, the largest Chinese community in Europe at the time. Between 1933 until 1942, there was a coordinated effort led by the Rotterdam police to count, record, and deport Chinese residents viewed as economically unproductive. The police regularly conducted night raids in Katendrecht, which Vivian Wong probably experienced, or at least, witnessed. Her frequent address changes – almost yearly – suggests a precarious living situation. She often lived above shops and small factories. Her second address, Delistraat 26a, was located above a trousers tailoring shop.

The card also reveals unknowns and ambiguities. For instance, we don’t know why she left her first employer, a certain “Breurman,” and whether she continued to work as a dienster, since her other addresses did not have names attached to them. We don’t know why she came to the Netherlands, or why she started living with her employer when she was only eight. And then there is the multi-directional network of Chinese migration to the Netherlands. Vivian Wong was born in North America, to a couple named Wong Quay and Bessie Brown. We know this because she listed their names on her marriage register. Her father was probably not a naturalized citizen of the US, due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Vivian Wong’s parents do not appear anywhere else in the municipal records, except in a passenger list. On 8th of April 1922, a certain “Wong Quay” travelled from New York through Rotterdam with two children, staying in Hotel Coomans. He was traveling to China. I’ve wondered if the man listed on the passenger list is the same man as Vivian Wong’s father. If so, why didn’t Vivian Wong make the final leg of the journey? In addition, why did Wong Quay left the U.S.? One possible factor to consider was the tightening of immigration laws since 1882. In 1924, the Johnson–Reed Act was enacted by the U.S. Congress, completely barring Chinese immigrants in the U.S. from citizenship, as well as new Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S.

A population registration card like this one provides some clues to a person’s lived experience, her family history, as well as her best efforts at surviving. Though we do not know Vivian Wong’s fate after 1937 – the year shown on the final address – the document provides yet another dimension to our understanding of an immigrant’s life in 1920s Katendrecht.

Story by Jiun Tan.

Jiun is a non-fiction and poetry writer. She is the founder of Life Stories Netherlands. She holds an MA in Public History from Central European University and a BA in History from NYU Abu Dhabi.