Embedding is not allowed.

Watch this video on YouTube

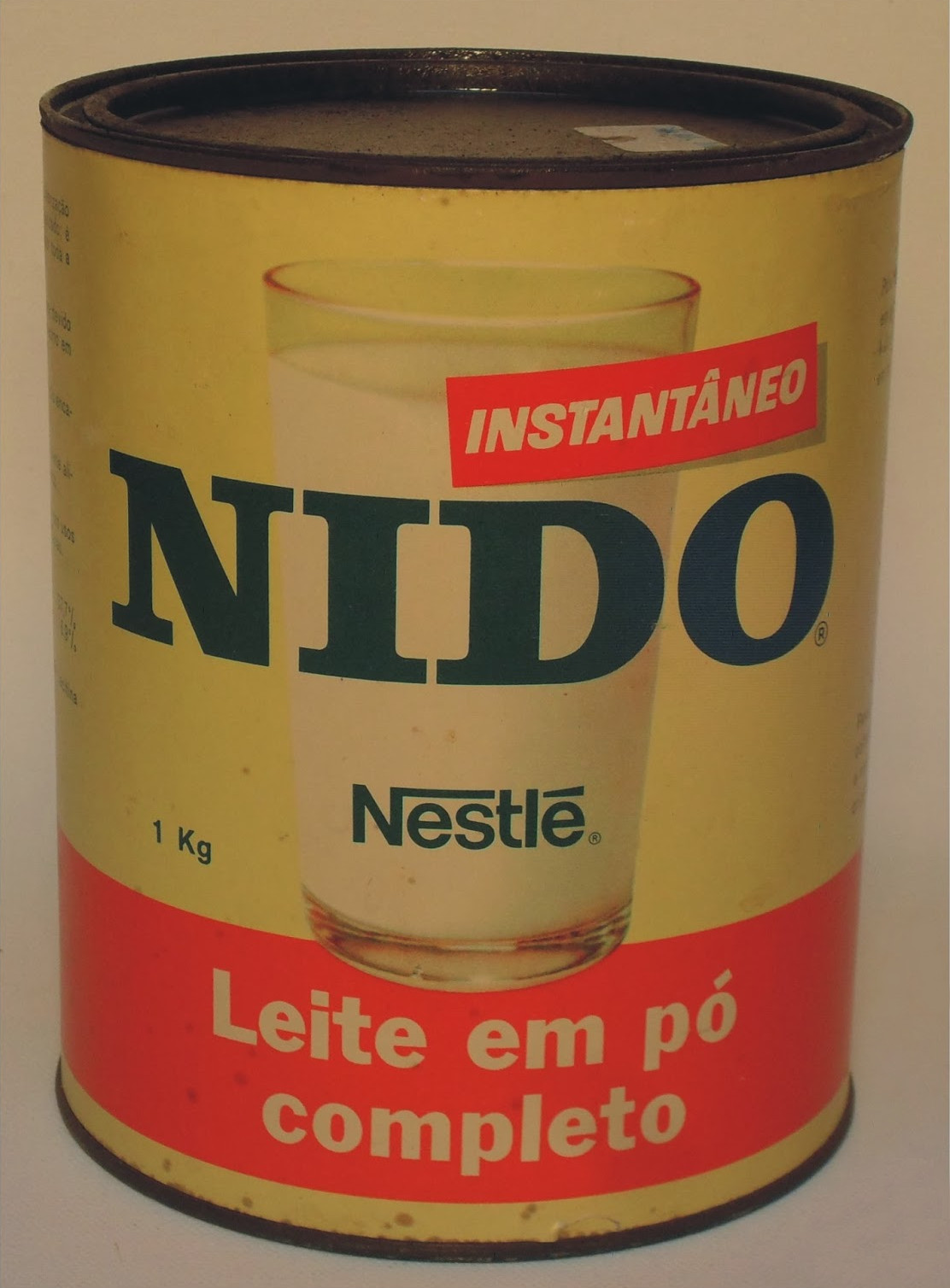

This is a typical and generic “Nido” powdered milk tin can, of the multinational Nestlé brand. The specific version we are looking at was commercialized in Angola in the late 1970s, shortly after the country’s independence from Portugal, reached in 1975. Due to the dramatic economic and industrial breakdown that Angola experienced in this period, shortage of foods and other basic goods were commonplace, as were experiences of hunger. In this framework, 1kg Nido cans were a necessity.

Today, Nido powdered milk is still sold throughout the world, however this 1kg tin can format seems to have been replaced with more ‘convenient’ single use plastic bags. It is therefore another ‘victim’ of evolving paradigms in industrial design trends in the subsequent decades. Criteria of economy, transportability and ‘discardability’, in such contexts of industrialized production, are prioritized against those of duration and preservability.

While a Nestlé powdered milk can is probably as mundane and generic as any industrial food sector object from a consumer perspective these particular cans gained popularity in the Portuguese-speaking world throughout the 1970s and 1980s. They acquired a certain aura of vintage and nostalgia, to the extent that they invoke not only a specific visual regime, but also a very particular sense of smell that can trigger personal emotions. For those who have consumed the product, the smell is probably as unforgettable as Jean-Baptiste Grenouille’s (the protagonist of Patrick Süskind’s famous novel) perfumes.

Thus, a 1970s Nido milk can emerges as an archiveable object at the intersection of brand and design history, and domestic consumer memories. However, my invocation of this object refers to the possibility of it becoming singularized into a personal object, transcending the generic collective memory into a specific, subjective, embodied account.

I think of the case of João, a former Angolan military who fought for Angolan independence and was later detained, alongside thousands of other Angolans, and accused of coup d’état barely two years after Angolan independence, in the aftermath of an internal conflict in the ruling party (the MPLA). During his several month-long sojourn in the Casa de Reclusão prison in Luanda, he was thrown into a cell with 4 beds and 8 inmates. The only available infrastructure for their physiological needs was a Nido can, which they shared collectively. “We did everything in the can”. For João, a Nido can very personally acquires a certain Proustian dimension of ‘flashbulb memory’, in its ability to transport him back to a specific place and time.

From this perspective, an industrial object such as a Nido can may acquire a transitional ontological condition, shifting from a generic consumption object to a nostalgic reference and finally, a source of traumatic memory. In the process, it navigates very distinct possibilities of un/archivability.

Story by Ruy Llera Blanes.

Ruy is an anthropologist based in Lisbon. He has conducted long term research in Angola, and more recently Mozambique, on religion, memory, human rights, social movements, environmental issues.